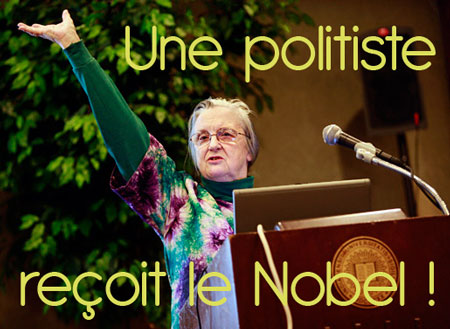

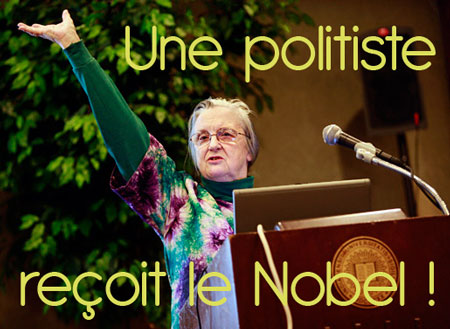

Le prix Nobel d'économie a été attribué lundi 12 octobre 2009 à l'Américaine Elinor Ostrom, née en 1933, et à son compatriote Oliver Williamson, né en 1932, pour leurs travaux sur "la gouvernance économique". "Ils veulent comprendre des organisations qui ne sont pas des marchés (...) et ils montrent comment ces institutions résolvent les conflits", a salué Tore Ellingsen, membre du comité Nobel, lors de l'annonce du prix à la presse. Pour la première fois dans l'histoire de cette récompense, créée en 1969, une femme est lauréate. Elinor Ostrom, professeur de science politique à l'Université d'Indiana (elle fut présidente de l’APSA en 1996-1997), "a démontré comment les co-propriétés peuvent être efficacement gérées par des associations d'usagers", précise le comité Nobel qui se félicite qu’elle ait "remis en cause l'idée classique selon laquelle la propriété commune est mal gérée et doit être prise en main par les autorités publiques ou le marché". Au cœur de ses thèses, l'idée donc que les marchés, ou l'Etat régulateur, ne constituent pas l'unique alternative à l'activité économique. Selon elle, les associations de consommateurs et d'usagers sont souvent mieux armées pour gérer les biens communs. Ses travaux montrent que les autochtones ont parfois un meilleur niveau d'expertise que les bureaucrates éloignés du terrain. En se fondant sur de nombreuses études sur la gestion par des groupes d'usagers des ressources en poissons, en élevage, les forêts ou les lacs, la lauréate américaine a montré que leur organisation était souvent meilleure que ne le croit la théorie économique. La lauréate a réagi à l’annonce de ce prix en déclarant que le monde était entré dans une nouvelle ère pour la reconnaissance des femmes. "J'ai bien conscience que c'est un honneur d'être la première femme" à recevoir le Nobel d'économie, "mais je ne serai pas la dernière", a-t-elle assuré...

Le prix Nobel d'économie a été attribué lundi 12 octobre 2009 à l'Américaine Elinor Ostrom, née en 1933, et à son compatriote Oliver Williamson, né en 1932, pour leurs travaux sur "la gouvernance économique". "Ils veulent comprendre des organisations qui ne sont pas des marchés (...) et ils montrent comment ces institutions résolvent les conflits", a salué Tore Ellingsen, membre du comité Nobel, lors de l'annonce du prix à la presse. Pour la première fois dans l'histoire de cette récompense, créée en 1969, une femme est lauréate. Elinor Ostrom, professeur de science politique à l'Université d'Indiana (elle fut présidente de l’APSA en 1996-1997), "a démontré comment les co-propriétés peuvent être efficacement gérées par des associations d'usagers", précise le comité Nobel qui se félicite qu’elle ait "remis en cause l'idée classique selon laquelle la propriété commune est mal gérée et doit être prise en main par les autorités publiques ou le marché". Au cœur de ses thèses, l'idée donc que les marchés, ou l'Etat régulateur, ne constituent pas l'unique alternative à l'activité économique. Selon elle, les associations de consommateurs et d'usagers sont souvent mieux armées pour gérer les biens communs. Ses travaux montrent que les autochtones ont parfois un meilleur niveau d'expertise que les bureaucrates éloignés du terrain. En se fondant sur de nombreuses études sur la gestion par des groupes d'usagers des ressources en poissons, en élevage, les forêts ou les lacs, la lauréate américaine a montré que leur organisation était souvent meilleure que ne le croit la théorie économique. La lauréate a réagi à l’annonce de ce prix en déclarant que le monde était entré dans une nouvelle ère pour la reconnaissance des femmes. "J'ai bien conscience que c'est un honneur d'être la première femme" à recevoir le Nobel d'économie, "mais je ne serai pas la dernière", a-t-elle assuré...

Télécharger le rapport scientifique du comité présentant les travaux de la politiste américaine

Scientific Background on the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2009 ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE compiled by the Economic Sciences Prize Committee of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2009/ecoadv09.pdf

En bref...

Governing the commons

Many natural resources, such as fish stocks, pastures, woods, lakes, and groundwater basins are managed as common property. That is, many users have access to the resource in question. If we want to halt the degradation of our natural environment and prevent a repetition of the many collapses of natural-resource stocks experienced in the past, we should learn from the successes and failures of common-property regimes. Ostrom’s work teaches us novel lessons about the deep mechanisms that sustain cooperation in human societies. It has frequently been suggested that common ownership entails excessive resource utilization, and that it is advisable to reduce utilization either by imposing government regulations, such as taxes or quotas, or by privatizing the resource. The theoretical argument is simple: each user weighs private benefits against private costs, thereby neglecting the negative impact on others. However, based on numerous empirical studies of natural-resource management, Elinor Ostrom has concluded that common property is often surprisingly well managed. Thus, the standard theoretical argument against common property is overly simplistic. It neglects the fact that users themselves can both create and enforce rules that mitigate overexploitation. The standard argument also neglects the practical difficulties associated with privatization and government regulation.

Failed collectivization and privatization

As an example of Ostrom’s concerns, consider the management of grasslands in the interior of Asia. Scientists have studied satellite images of Mongolia and neighboring areas in China and Russia, where livestock has been feeding on large grassland areas for centuries. Historically, the region was dominated by nomads, who moved their herds on a seasonal basis. In Mongolia, these traditions were largely intact in the mid-1990s, while neighboring areas in China and Russia – with closely similar initial conditions – had been exposed to radically different governance regimes. There, central government imposed state-owned agricultural collectives, where most users settled permanently. As a result, the land was heavily degraded in both China and Russia. In the early 1980s, in an attempt to reverse the degradation, China dissolved the People’s Communes and privatized much of the grassland of Inner Mongolia. Individual households gained ownership of specific plots of land. Again, as in the case of the collectives, this policy encouraged permanent settlement rather than pastoral wandering, with further land degradation as a result. As satellite images clearly reveal, both socialism and privatization are associated with worse long-term outcomes than those observed in traditional group-based governance.

Failed modernization

There are many other examples which indicate that user-management of local resources has been more successful than management by outsiders. A striking case is that of irrigation systems in Nepal, where locally managed irrigation systems have successfully allocated water between users for a long time. However, the dams – built from stone, mud and trees – have often been primitive and small. In several places, the Nepalese government, with assistance from foreign donors, has therefore built modern dams of concrete and steel. Despite flawless engineering, many of these projects have ended in failure. The reason is that the presence of durable dams has severed the ties between head-end and tail-end users. Since the dams are durable, there is little need for cooperation among users in maintaining the dams. Therefore, head-end users can extract a disproportionate share of the water without fearing the loss of tail-end maintenance labor. Ultimately, the total crop yield is frequently higher around the primitive dams than around the modern dams. Both of the above-mentioned failures refer to economically poor regions of the world. However, the lessons are much more far-reaching. Ostrom’s first study concerned the management of groundwater in parts of California and also highlighted the role of users in creating workable institutions.

Active participation is the key

While Ostrom has carried out some field work herself, her main accomplishment has been to collect relevant information from a diverse set of sources about the governance – successful and failed – of a large number of resource pools throughout the world and to draw insightful conclusions based on systematic comparisons. The lesson is not that user-management is always preferable to all other solutions. There are many cases in which privatization or public regulation yield better outcomes than user management. For example, in the 1930s, failure to privatize oil pools in Texas and Oklahoma caused massive waste. Rather, the main lesson is that common property is often managed on the basis of rules and procedures that have evolved over long periods of time. As a result they are more adequate and subtle than outsiders – both politicians and social scientists – have tended to realize. Beyond showing that self-governance can be feasible and successful, Ostrom also elucidate the key features of successful governance. One instance is that active participation of users in creating and enforcing rules appears to be essential. Rules that are imposed from the outside or unilaterally dictated by powerful insiders have less legitimacy and are more likely to be violated. Likewise, monitoring and enforcement work better when conducted by insiders than by outsiders. These principles are in stark contrast to the common view that monitoring and sanctioning are the responsibility of the state and should be conducted by public employees. An intriguing outcome of these field studies concerns the willingness of individual users to engage in monitoring and sanctioning, despite only modest rewards for doing so. In order to ascertain more about individuals’ motivations for taking part in the enforcement of rules, Ostrom has conducted innovative laboratory experiments on cooperation in groups. A major finding is that many people are willing to incur private costs in order to sanction free-riders.

Article à lire ! « Revisiting the Commons: Local Lessons, Global Challenges », Science, April 1999, Vol. 284. no. 5412, pp. 278 – 282 http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/284/5412/278

Page web http://www.cogs.indiana.edu/people/homepages/ostrom.html

A propos de...

Education

B.A. (with honors), Political Science, UCLA, 1954 M.A., Political Science, UCLA, 1962 Ph.D., Political Science, UCLA, 1965

Present Positions

Arthur F. Bentley Professor of Political Science, Indiana University, Bloomington Senior Research Director, Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis, Indiana University, Bloomington Founding Director, Center for the Study of Institutional Diversity, Arizona State University, Tempe Professor (part-time), School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University, Bloomington Awards Ostrom is a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_National_Academy_of_Sciences and past president of the American Political Science Association http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Political_Science_Association . In 1999 she became the first woman to receive the prestigious Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johan_Skytte_Prize_in_Political_Science and in 2005 received the James Madison Award by the American Political Science Association. In 2008, she received the William H. Riker Prize in political science http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_H._Riker, and became the first woman to do so. In 2009, she received the Tisch Civic Engagement Research Prize from the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service at Tufts University http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tufts_University .

Photo: Elinor Ostrom delivering a lecture at Indiana University, Bloomington, July 2008.

Courtesy of Indiana University

Le prix Nobel d'économie a été attribué lundi 12 octobre 2009 à l'Américaine Elinor Ostrom, née en 1933, et à son compatriote Oliver Williamson, né en 1932, pour leurs travaux sur "la gouvernance économique". "Ils veulent comprendre des organisations qui ne sont pas des marchés (...) et ils montrent comment ces institutions résolvent les conflits", a salué Tore Ellingsen, membre du comité Nobel, lors de l'annonce du prix à la presse. Pour la première fois dans l'histoire de cette récompense, créée en 1969, une femme est lauréate. Elinor Ostrom, professeur de science politique à l'Université d'Indiana (elle fut présidente de l’APSA en 1996-1997), "a démontré comment les co-propriétés peuvent être efficacement gérées par des associations d'usagers", précise le comité Nobel qui se félicite qu’elle ait "remis en cause l'idée classique selon laquelle la propriété commune est mal gérée et doit être prise en main par les autorités publiques ou le marché". Au cœur de ses thèses, l'idée donc que les marchés, ou l'Etat régulateur, ne constituent pas l'unique alternative à l'activité économique. Selon elle, les associations de consommateurs et d'usagers sont souvent mieux armées pour gérer les biens communs. Ses travaux montrent que les autochtones ont parfois un meilleur niveau d'expertise que les bureaucrates éloignés du terrain. En se fondant sur de nombreuses études sur la gestion par des groupes d'usagers des ressources en poissons, en élevage, les forêts ou les lacs, la lauréate américaine a montré que leur organisation était souvent meilleure que ne le croit la théorie économique. La lauréate a réagi à l’annonce de ce prix en déclarant que le monde était entré dans une nouvelle ère pour la reconnaissance des femmes. "J'ai bien conscience que c'est un honneur d'être la première femme" à recevoir le Nobel d'économie, "mais je ne serai pas la dernière", a-t-elle assuré...

Le prix Nobel d'économie a été attribué lundi 12 octobre 2009 à l'Américaine Elinor Ostrom, née en 1933, et à son compatriote Oliver Williamson, né en 1932, pour leurs travaux sur "la gouvernance économique". "Ils veulent comprendre des organisations qui ne sont pas des marchés (...) et ils montrent comment ces institutions résolvent les conflits", a salué Tore Ellingsen, membre du comité Nobel, lors de l'annonce du prix à la presse. Pour la première fois dans l'histoire de cette récompense, créée en 1969, une femme est lauréate. Elinor Ostrom, professeur de science politique à l'Université d'Indiana (elle fut présidente de l’APSA en 1996-1997), "a démontré comment les co-propriétés peuvent être efficacement gérées par des associations d'usagers", précise le comité Nobel qui se félicite qu’elle ait "remis en cause l'idée classique selon laquelle la propriété commune est mal gérée et doit être prise en main par les autorités publiques ou le marché". Au cœur de ses thèses, l'idée donc que les marchés, ou l'Etat régulateur, ne constituent pas l'unique alternative à l'activité économique. Selon elle, les associations de consommateurs et d'usagers sont souvent mieux armées pour gérer les biens communs. Ses travaux montrent que les autochtones ont parfois un meilleur niveau d'expertise que les bureaucrates éloignés du terrain. En se fondant sur de nombreuses études sur la gestion par des groupes d'usagers des ressources en poissons, en élevage, les forêts ou les lacs, la lauréate américaine a montré que leur organisation était souvent meilleure que ne le croit la théorie économique. La lauréate a réagi à l’annonce de ce prix en déclarant que le monde était entré dans une nouvelle ère pour la reconnaissance des femmes. "J'ai bien conscience que c'est un honneur d'être la première femme" à recevoir le Nobel d'économie, "mais je ne serai pas la dernière", a-t-elle assuré...